On Carlos

“Don’t let him sleep on your bed, or you’ll never get a good night’s sleep again.”

A very young Carlos investigates an empty salsa container sitting on one of my foam cow-cubes, circa 1996.

In the spring of 1995, I was a newly-graduated 22-year-old fresh from four years of smack dab in the middle of Connecticut, on my way out to a scantily-paying job in Minneapolis. The only people I knew in Minnesota were graduating and would leave town two weeks later. I was on my own. My first job, auspiciously, was at a magazine I admired greatly, helping to take their editorial vision into a new medium: the World Wide Web, still novel enough to capitalize.

I moved into a 40-unit apartment building and took what alleged to be a part-time, off-hours gig as the building super. The job amounted to vacuuming the halls, answering calls to show empty apartments, unclogging toilets and unclogging toilets. Also, unclogging toilets. The old couple to whom I directly answered had managed to make themselves middle management by hiring me (for half rent) and took great pains to chastise me whenever I left the building and was unavailable for toilet uncloggings. Building a website in 1995 was not a straightforward exercise. More than once I slept under my desk rather than hike back to my apartment.

The warm and loving social circles in which I’d grown and laughed at college had dissipated after graduation, and I was keenly aware of my distance from them in time and space even as I pushed a vacuum up and down dark halls and picked up enough HyperText Markup Language to flummox the print publishers at my day job.

Into this solitary existence my mom offered me two things: a small orange kitten and advice to keep it out of my room at night.

I drove down to Madison and met the kitten, who we erroneously believed to be female. Pale orange, like a faintly unripe clementine. Skittish, playfully ferocious, fell asleep nearly as fast as waking up at a full sprint across the house: I named ‘her’ Carla, on a whim, and bundled ‘her’ back to my corner apartment off Loring Park.

The sun went down. I brushed my teeth, checked to make sure the kitten’s food, water and litter box were all where they needed to be (outside my room) and closed the door. I lay down in bed.

<scratch> </scratch>

<mew> </mew>

<scratchscratch></scratchscratch>

<MEW/> <MEW/>

The orange kitten threw itself against the door, batting and pleading while I lay alone on my futon, imagining the dark apartment and what terrors a small animal alone might envision. The mewling was plaintive and high pitched, echoing off the wood floors and close walls. We were each alone on opposite sides of a dark wood door. My mom’s advice ran through my head, but it became clear to me that as well-intentioned as it was, I wasn’t going to follow it. I got up, cracked the door open, and allowed that orange cat to come in and ruin the first of many, many nights’ sleep.

And that was Carlos.

I figured out his sex in relatively short order – cats are fuzzy, but some features grow increasingly unambiguous – and his likes (glittery, fuzzy foil balls, which he would fetch and return to me to throw over and over) and dislikes (solitude, vacuum cleaners). He began to grow from a wobble-footed kitten into a long, lanky cat, and wrecked a Papasan(™) chair by refusing to stop pissing in it while I was at work.

After being unexpectedly laid off, I had a choice: stay in the Twin Cities or head east to Boston, where a sizable percentage of college friends had settled and where a small web-design startup needed someone. I began packing for the move.

This soon after college, I could still fit every book, pan and dorm-room-sized piece of furniture into a VW Rabbit and one heavily-loaded pickup truck. I would drive out in my mom’s truck, drive back to Wisconsin, and then return in my car. Carlos stayed at my mom’s house in Madison while I did the initial run, returned, and then got in the car to head out again. After an hour of very vocal complaining, he eventually accepted that the car ride was going to continue whether or not he liked it. In a strategic error, I opened his cat carrier while underway, thinking that he would enjoy the freedom to move around the cabin. Instead, he immediately wedged himself under the driver’s seat and refused to budge.

We stayed in a cheap motel with no explicit pet policy, so I smuggled him and a shoe box of kitty litter into the room on the down low. Surely, I rationalized, this was not the worst moral violation a roadside motel has ever seen. In the morning, we set off again, each only slightly refreshed. Another hour’s moaning later, he once again hushed and watched the Pennsylvania hills roll past.

Early experiments with photo manipulation and cat pictures, circa 1998

In Boston, Carlos grew. He accepted an early roommate’s feisty, mercurial, car-wounded cat as he would every other co-resident cat for the rest of his life: by knuckling under and allowing her to take the top spot. He began a lifelong obsession with high places, from which he could see everything and never be surprised. I fed him on top of the refrigerator in order to keep his food separate from the other cats who lived with us over the years. In order to get to the fridge, he had to make one good jump off the corner of the counter … or, as he eventually began to prefer, he’d use any conveniently-placed human shoulders as a Prince-of-Persia platform from which to launch or ricochet to his dinner. He and I knew the routine: I would stand between him and the fridge and dip one shoulder towards him, at which point I’d feel 10 pounds of elastic cat land on my scapula and spring airborne again in one motion, confident as any floor gymnast.

Sleeping, armadillo-style

He ate broccoli leaves and shrimp from leftover sushi, and subtly flaunted his free-feeding at our fat cat Lucy, too heavy to reach his food dish atop the fridge. In winter months, he insisted on sleeping in the crook of my arm, always closest to my face, despite my many attempts to encourage him to sleep at the small of my back instead. Humans who shared my bed learned that Carlos could be shut out of the bedroom for only short periods, after which the scratching and complaining began in earnest. I’d inevitably shrug myself across the room and crack the door open. Carlos suffered being displaced from the crook of my arm calmly, as if he knew that he would outlast almost every one of these temporary interlopers.

Lucy and Carlos, circa 2008

When a cat-less roommate moved in, I went to the local ASPCA shelter and adopted a small, round tuxedo cat who came with the unbearable name ‘Mittens,’ and who I quickly renamed Lucy, for the Peanuts’ raven-haired beauty with the devastating left hook. Lucy took charge; Carlos slipped easily into the beta-cat role.

I became utterly accustomed to sleeping with my bedroom door a hand’s-width open, even when visiting friends with no cats. A girlfriend in those years once said, observing my relationship with Carlos and his with me, that we were close without being overly sentimental. “If he could talk,” she said, “I bet he’d call you ‘boss,’ not ‘Dad.’” That felt right to me; he was not my child nor I his parent. We were a companionable team.

Dozing with Kate

This was not to say his behavior was consistently good. One roommate nicknamed Carlos “Wily Fucker,” after a particularly egregious shrimp-snatching. Another needed to put a liquid-proof mattress cover on his bed after Carlos began peeing on it, to my vicarious shame. He once inexplicably consumed most of a bowl of spring tulips a friend left out on a table. Once, during a roommate’s move-in, I thought Carlos had slipped out onto the Somerville streets. I spent 45 minutes frantically walking the surrounding blocks and making the clicking sound that called him to dinner, only to discover he’d been asleep in our apartment the whole time, under “the hideous chair” and its draped slip cover. After purchasing a second Papasan, then a replacement cushion, and then another replacement cushion, I decided that I could have this cat or I could have a urine-free cheap chair shaped like a satellite dish, but not both. I kept Carlos.

He continued to play fetch with foil balls, and became obsessed with a small blue bathmat. He sprinted through the apartment like a thrown ping-pong ball, skid wild-eyed to a halt on the mat to feel it slide on the floor, and then sprang off again, furling the mat behind him he scrabbled on the wood floor for purchase. I would spread out the blue mat just in time for him to screech to a halt on it again, his tail lashing before another sprinters’ start.

Carlos and Lightning in a rare moment of detente.

I pursued Kate down to Philadelphia. She and her cat, Lightning, moved into the new apartment two weeks before Carlos, Lucy and I moved down. In cat terms, this meant that Lightning called ‘dibs’ on the bedroom and guest room while Carlos and Lucy patrolled the kitchen and living room. That winter, Carlos made it onto the bed only by stealth, good timing, or particularly-well-executed parabolae… but make it he did.

Carlos atop a cabinet in NH

The five of us moved up to New Hampshire, where Lucy honed her skills at small-animal assassination. Carlos enjoyed brief trips outside but preferred the more controlled environment indoors where he could perch on top of open doors, doze in the sun and reliably find me. Country living was all well and good, but did not rival consistency in his estimation. His blue bathmat slid marvelously on the wood floors.

Carlos and newborn Piper, in NYC

We moved to New York City, where Lightning died and Piper, our first kid, showed up. Lucy mostly found the baby irritating but enjoyed the soft things on which she could nap, while Carlos seemed gently intrigued and unfailingly tolerant of this new roommate. At particularly bad grabbing hands or wailing shrieks he would drop his ears and slink away, but never raised a paw to her.

Carlos and Piper napping, 2011

From New York we moved back to Wisconsin, where after a brief stay on my mom’s farm, we moved into the house in Madison in which I’d been a teenager: the same house in which Carlos was born. Lucy wound up preferring country life and returned to the farm, where she lived out her last year and a half providing plenty of work to the Death of Mice. Carlos stayed with us, ambling, eating, tickling my face with his whiskers during winter nights and melting into orange butter on the couch during summer days.

Triple napping with Syd, May 2012

He was 17 years old when various ailments began to show up: Inflammatory Bowel Disease, which would slowly rob him of his ability to get nutrients from his food. Arthritis, which made his jumps slower and gradually painful. Kidney disease, which made his urine slightly less noxious but slightly more frequent in annoying locations around the house. Each ailment came with a prescription that alleged to slow it down, and we began pilling him daily and giving him subcutaneous IV fluids periodically, despite his clear dislike for them. We marveled as he nabbed mice.

Carlos and Syd, Apr 2014

Last summer, at 19 years old, his breathing became labored and I whisked him off to the hospital, where they tapped a maple tree’s worth of fluid from his chest and added daily diuretics to his pill regimen to combat congestive heart failure. I switched him from a vet that required a stressful car ride to a vet who made house calls on her bicycle. She gently examined him and said that we’d be lucky to see him alive at Christmas. I began to feed him anything he wanted: “nasty wet food,” bonito flakes, frozen shrimp thawed and prescription food purchased. He purred, tucked into them, and snuggled deep into my arm every night as the snow piled down outside. He began to shrink, what few pounds he had slowly sublimating away like an old, old ice cube in the back of the freezer.

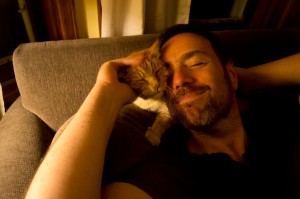

John and Carlos, August 2012

John, visiting from New Hampshire, bought Carlos a heating pad that we placed at the highest spot he could reliably climb to: the top of the couch cushions, from where he could watch the traffic on the street. I began to buy empty gelatin capsules from the pharmacy in which I could consolidate his twice daily pills. While Kate and various neighbors could fight his medicines into him after several tries, I got fast enough and generally calm enough to get a capsule and two pills down him in under 10 seconds, on the first try. He continued to shrink, and his jumps grew wobbly, but we reached the New Year and felt lucky. We reached my birthday and felt lucky. We reached spring, and switched out our storm windows for screens, and watched him sniff the air and take brief trips out to lap at rain water and bask on our front steps, and we felt lucky.

Sunning, 2013

In every year before this, spring meant that he stopped sleeping in bed with us, but this spring, he never stopped. Every night he’d meet us there, waiting for me to arrange my arms to allow him to settle against my chest. When kids, both our own and our neighbors’, would come by and manhandle him, he put up with it with his usual good grace, but would walk away sooner. Incredibly, he captured another several mice in quick succession, eating half of one and none of the second.

Nibbling on a shrimp, June 7

Two weeks ago, I noticed his eating starting to slow. He left “nasty wet food” in his dish; the last two shrimp were left alone and unshredded to slowly dry out. In the last week, the muscles in his legs began to obviously slough away, and his walk went from just unsteady to a drunkard’s wobble. In the last few days, he stopped switching sides when I rolled over in bed, and simply lay out between Kate and me. His purr continued, and would frequently be the first sound I heard in the morning, but during the rest of the day he began to respond more and more slowly.

Sharing a moment

Our vet always called me back, heard my updates, encouraged me to trust my intuition about him and marveled with us at his diligent (and successful) hunting. On Tuesday, it became clear that food had utterly lost its appeal to him. The only comfort he seemed to take was in drinking rain water, feeling the sun on his fur and sleeping in bed with me. I called and made an appointment: Thursday afternoon, June 25th. Our 10th wedding anniversary and the soonest our vet could make it to us.

During the 36 hours leading up to her arrival, I was a sodden, sobbing mess, emotionally unsure of this choice even while rationally certain that this sharp decline was as clear a signal as he could give. My mom asked whether I could or should let him die on his own terms rather than put him to sleep; the question stayed with me. I did not have an answer that felt good to me. I had for months selfishly hoped that his heart would take him out of this world quickly, mercifully and without my needing to intervene. Why wouldn’t I wait a little longer for him to die on his own?

I showered him with fresh food and bonito flakes, at which he would desultorily lick once or twice before teetering away. We tried giving him a little fluid via IV, but gave up when it was clear that it was stressing him further. I spent the day working on my laptop on the couch, holding my head against his and waiting for his purr. Each time it took longer and longer to surface.

Carlos, on his last sunny day, June 25, 2015

An hour before she arrived, the rain cleared and the sun came out. I brought Carlos outside along with his blue bathmat, a bowl of bonito flakes, a tall sprig of catnip and a dish of rainwater. He sat, blinking in the sun, eyed the treats and laboriously turned around.

There was in that instant, plainly, nothing more here that he wanted. Any selfish hesitation I’d had or fantasy that a spontaneous death would be better evaporated. For the past months, I had imagined that I could come home, discover him dead and count it a blessing. Instead, I lay in the warm grass next to him, stroked his terribly reduced little body, and spoke to him as calmly as I could.

In the grass

“I wouldn’t let you sleep alone that first night, and I’m not going to let you die alone now.”

Our vet came. We sat and talked for a while in our back yard before she reached for her kit. His end was pain free and calm, lying in the grass, and in the end we arranged his body in his blue bathmat and spoke of the miracle of death. A closed-room mystery: where does the life go when it is no longer here? My hand on his stilled chest kept thinking it felt the vibration of his purr, minutes after his heart had ceased to beat.

Having cried close to continuously for the previous 36 hours, I stopped then and haven’t since. The waiting was over.

With his water fountain turned off, the house seems eerily quiet, and I keep expecting to hear tapping claws on the floor and the soft bounce as he jumps onto the bed.

The bed… the bed feels like a mouth with a tooth pulled. My arms keep readying themselves for an orange cat who is not there.

I’m mourning a long-lived companion who has passed on – a gentle, tolerant cat who liked high places, people, food and playing – but I think on some level I’m also mourning the passage of 20 years. A cat’s lifetime can be a yardstick to hold up against one’s own time in this world. I was young and independent, fearful and alone, both, when I got that little mis-sexed kitten, and I will never be that young man again. We may have other cats in the future, but I have grown wise, now, and protective of my sleep. The particular follies I had back then have passed, for better and worse. I don’t know that I would let another cat into my bedroom so easily again.